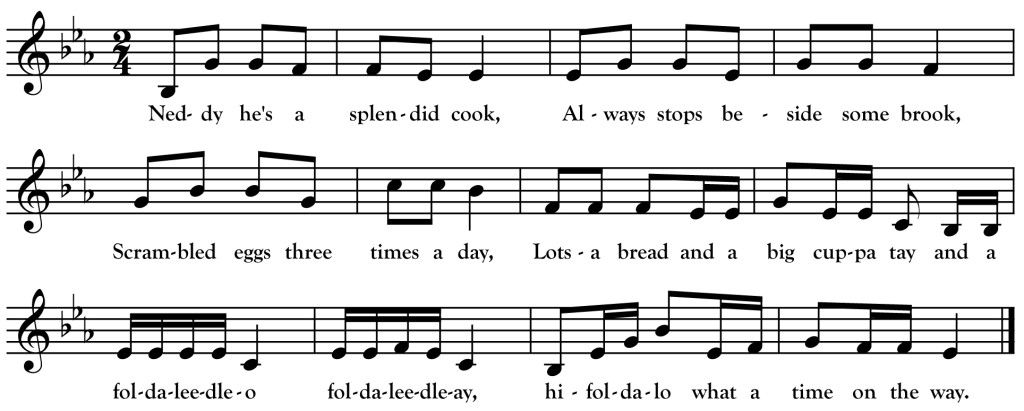

What a Time on the Way

Neddy he’s a splendid cook,

Always stops beside some brook,

Scrambled eggs three times a day,

Lotsa bread and a big cuppa tay,

And a fol-da-lee-dle-o, fol-da-lee-dle-ay,

Hi-fol-da-lo, what a time on the way.

Now that the harvest days are through,

To old D-kotey we will bid you adieu,

Back to the jack pines we will go,

To haul these saw logs in the snow.

And a fol-da-lee-dle-o, fol-da-lee-dle-ay,

Hi-fol-da-lo, what a time on the way.

______________________________________________________________

Folklorist Robert Winslow Gordon could not resist making a few song-collecting detours as he traveled from Berkeley, California to a new job at Harvard in 1924. He later recalled that he had spent “too much time on the way, especially in Northern Minnesota, where I got a number of good things.” The good things he got were several recordings of songs sung by of members of the Phillips family of Akeley, Minnesota.

Gordon recorded the above song fragment from Israel Lawrence [Lorentz] Phillips (1883-1967). It is quite similar in content and, to some extent, melody to another song called “How We Got Up to the Woods Last Year” that was collected in Ontario and Michigan. “What a Time on the Way” references the common practice among itinerant young men to work the harvest in the Dakotas (here referred to as “old D-kotey”) before returning to a winter job in a Minnesota logging camp.

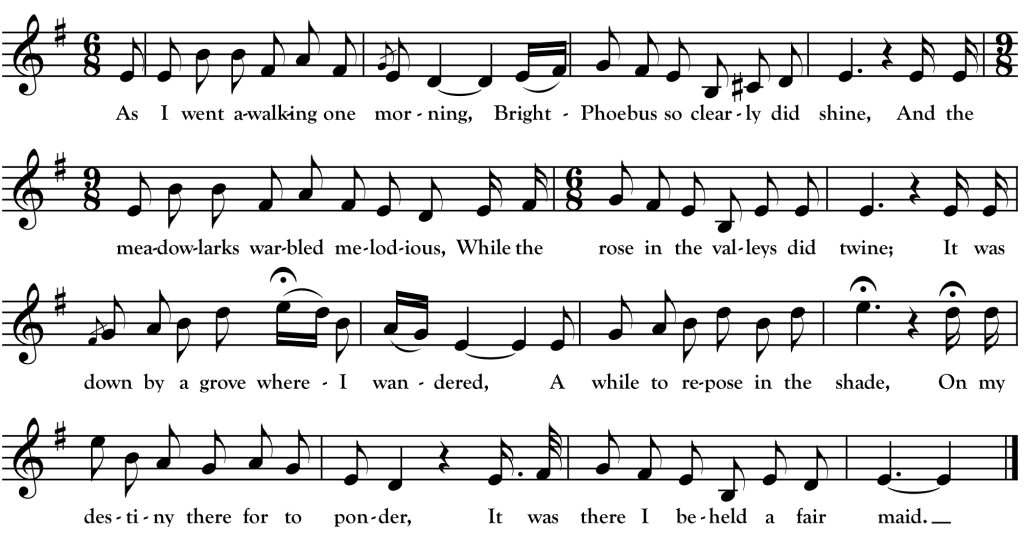

This song’s chorus also brings to mind one of the earliest accounts I have found of lumber camp singing in Minnesota. Any aficionado of traditional folk song will be familiar with the type of nonsense syllables (“fol-da-lee-dle-o,” etc.) here. Perhaps it was a similar chorus that confused J. M. Tuttle of Harpers New Monthly Magazine who witnessed the evening activities in “Moses’s Camp” near the East Branch of the Rum River in March 1867:

Thirty fine-looking, healthy, robust, well-behaved men sat down at the supper-table, and who, when their appetites were sated, broke up the evening in various ways. Some mended their clothes, some darned their socks, some, using the sinews of the deer, obtained of the Indians, for thread, repaired their moccasins, while others employed their time in reading. The hours were relieved, too, by a little entertainment in the shape of music and dancing. One young man, who had swung the axe all day, rosined up his bow and gave us few lively airs on his fiddle, while two other logmen, who had tramped in twelve inches of snow since the early morn, engaged in a “double shuffle,” or something of the kind, on one of the planks of the floor. A pleasant-voiced son of Erin sang two or three songs, substituting simple musical sounds where he was unable to recall the words. Others still filled the intervals between the music with conversation on a variety of topics, breaking out now and then in loud, hearty laughter.

(J. M. Tuttle, Harpers New Monthly Magazine Vol 36 Issue 214“Minnesota Pineries” edited by Henry Mills Alden, March 1868)