Sentenced to Death

With the Sign of the Cross on my forehead, as I kneel on this cold dungeon floor,

As I kneel at your feet, reverend father, with no one but God to the fore,

I have told you the faults of my boyhood—the follies and sins of my youth,

And it’s now from this crime of my manhood I speak with the same open truth.

You see, sir, the land was our people’s for ninety long years, and their toil,

What first was a bare bit of mountain brought into good wheat-bearing soil,

’Twas their hands rose the walls of our cabin, where our children were borned and bred,

Where our wedding’s an’ christening’s was merry, where we weeped and keened over our dead.

We were honest and fair to the landlord-we paid him the rent to the day,

And it wasn’t our fault if our hard sweat they squandered and wasted away,

In the cards, and the dice, and the racecourse, and often in deeper disgrace,

That no tongue could relate without bringing a blush to an honest man’s face.

But the day come at last that they worked for, when the castles, the mansions and lands,

They should hold but in trust for the people, ’til their shame passed away from their hands,

And our place, sir, too, went to auction–by many the acres were sought,

And what cared the stranger that purchased, who made him the good soil he bought?

The old folks were gone—thank God for it—where troubles or cares can’t pursue,

But the wife and the children—Oh Father in Heaven—what was I to do?

Sure I thought, I’ll go speak to the new man, and tell him of me and of mine,

And the trifle that I’ve put together I’ll place in his hand as a fine.

The estate is worth six times the money, and maybe his heart isn’t cold,

But the scoundrel that bought the thief’s penny-worth was worse than the pauper that sold.

Well I chased him to house and to office, wherever I thought he’d be met,

And I offered him all he’d put on it—but no, ’twas the land he should get,

I prayed as men only to God pray—my prayers they were spurned and denied,

And no matter how just my right was, when he had the law at his side.

I was young, and but few years was married to one with a voice like a bird,

When she sang the songs of our country, every feeling within me was stirred,

Oh I see her this minute before me, with a foot wouldn’t bend a croneen,

And her laughing eyes lifted to kiss me—my charming, my bright-eyed Eileen!

’Twas often with pride that I watched her, her soft arms folding our boy,

Until he chased the smile from her red lip, and silenced the song of her joy,

Whisht, father, have patience a minute, let me wipe the big drops from my brow,

Whisht, father, I’ll try not to curse him; but I tell you, don’t preach to me now.

Well, he threatened, he coaxed, he ejected; for we tried to cling to the place,

That was mine, yes, far more than ’twas his, sir; I told him so up to his face,

But the little I had melted from me in making the fight for my own,

And a beggar, with three helpless children, out on the wide world I was thrown.

And Eileen would soon have another—another that never drew breath,

The neighbors were good to us always—but what could they do against death?

For my wife and her infant before me lay dead, and by him they were killed,

As sure as I’m kneeling before you, to own to my share of the guilt.

Well I laughed all consoling to scorn, I didn’t mind much what I said,

With Eileen a corpse in the barn, with a bundle of straw for a bed,

Sure the blood in my veins boiled to madness—do you think that a man is a log?

Well I tracked him once more—’twas the last time—and shot him that night like a dog.

Yes, I shot him, I did it, but father, let them that makes laws for the land,

Look to it, when they come to judgment, for the blood that lies red on my hand,

If I drew the piece, ’twas them primed it, that left him stretched cold on the sod,

And from their bar, where I got my sentence, I appeal to the bar of my God.

For the justice I never got from them, the right in their hands is unknown,

Still I say sir, at last, that I’m sorry I took the law into my own,

That I stole out that night in the darkness, whilst mad with my grief and despair,

And I drew the black soul from his body, not giving him time for a prayer.

Well, it is told, sir you have the whole story, God forgive him and me for our sins,

My life now is ended—oh father, for the young ones, for them life begins,

You’ll look to poor Eileen’s young orphans? God bless you and now I’m at rest,

And resigned to the death that tomorrow is staring me straight in the face.

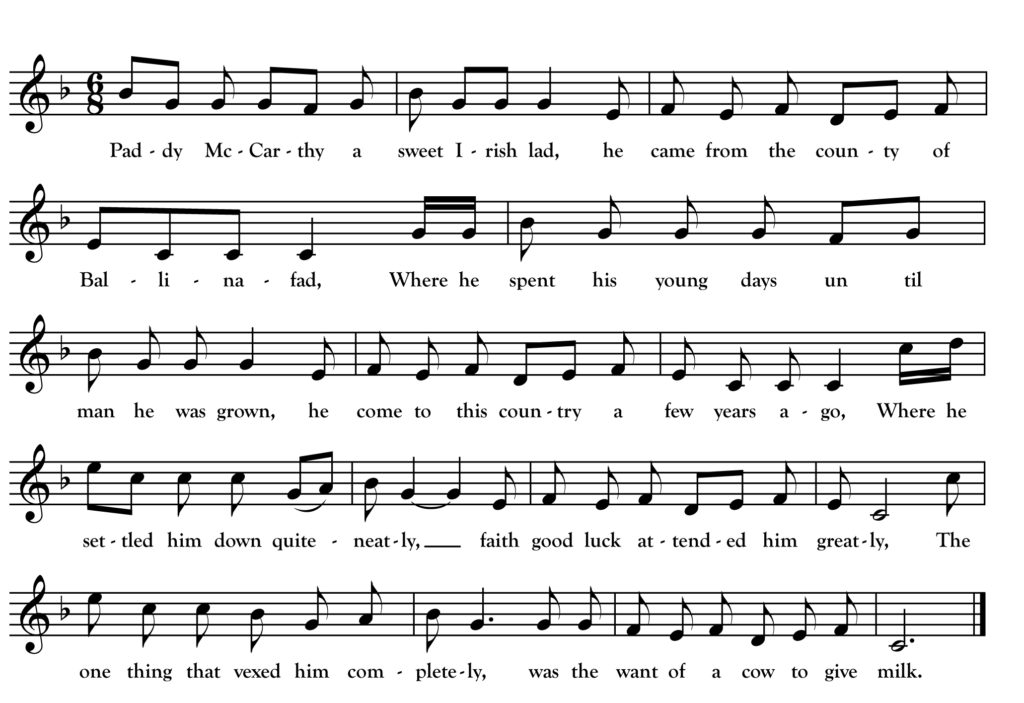

This incredibly grim and moving song depicting an Irish tenant farmer confessing to the murder of his landlord appeared as a poem in an 1886 edition of Minneapolis’ Irish Standard newspaper. It was written by a Cork woman, Katharine Murphy, who published it in Ireland under a pseudonym in the nationalist newspaper The Nation ten years prior. The only known sung version of the poem is one collected in Beaver Island, Michigan from Andrew “Mary Ellen” Gallagher by Alan Lomax (listen to first part here and second part here). Above, I have transcribed Gallagher’s version and filled in some stanzas using the Irish Standard. For more information on this remarkable song including the Irish Standard excerpt and the Gallagher recording, see this post in the “Caught My Ear” blog by the American Folklife Center’s Stephen Winick.