Sweet Mary Jane

My true love’s name was Mary Jane,

Her epitaph reveals the same,

Her grace and charm I will proclaim,

Through all my days moreover,

Where could you find a fairer dame,

And search this wide world over.

“My love and I we did agree,

That when I would return from sea,

We’d go straightway and married be,

And live a life of leisure,

No more to face the stormy sea,

In quest of gold and treasure.

“But I had not gone across the main,

When cruel death had my companion slain,

The pride and beauty of the plain,

In her cold grave lay moldering,

And our fond plan was all in vain,

Amid the ruins smoldering.

“I am distressed what shall I do,

I’ll roam this wide world through and through,

I’ll sigh and sing for sake of you,

My days I’ll spend in mourning,

And in my dreams I’ll wander through,

The lane that knows no turning.

A sad and beautiful song this month that was collected from several singers in eastern Canada and that was also in the repertoire of Minnesota singer Michael Dean. In most Canadian versions, the lost lover’s name is “Phoebe” (or “Bright Phoebe”). In Maine, singer Carrie Grover learned it as “Sweet Caroline” while in Minnesota, Dean sang “Mary Jane” and printed it as “Sweet Mary Jane” in his 1922 songster The Flying Cloud.

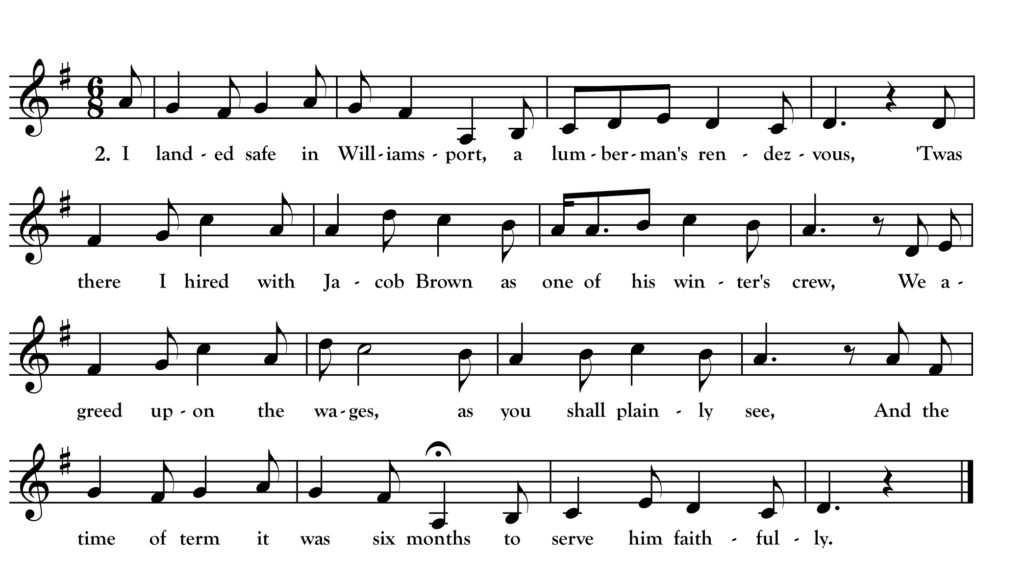

The above melody is my best effort to transcribe the richly ornamented version sung by New Brunswick singer Angelo Dornan. We do not know what melody Dean used but most collected melodies, including Dornan’s, show a resemblance to the famous “Greensleeves” melody. Dornan’s striking twists and turns make his air refreshingly unique. For text, I subbed in Dean’s first line and made a couple small changes of my own but otherwise stayed close to Dornan’s version including its unique six-line poetic structure (most other versions have four-line stanzas). Dornan sang two additional verses to what appears here and a transcription of his full version appears in Helen Creighton’s Maritime Folk Songs.