Duluth in Eighty-Two

To tell the truth I came to Duluth in eighteen eighty-two,

The Windsor was the best hotel on Superior Avenue,

I walked right in to the lion’s den, the Gilbreths kept the joint,

Then nix come arouse to the Cap Norris house or Minnesota Point.

It may seem queer but I did not hear of any iron range,

But the big pine trees, bent to the breeze; oh, mister, what a change,

No ore docks then but now, gentlemen, look up along the bay,

See the docks of ore, hear the whistles roar, as the big boats steam away.

No big flour mills high as the hills; no Duluth Board of Trade,

Just two elevators and no speculators—the wheat was just one grade,

No electric light, to daze the sight; no monster areal bridge,

No electric railway across St. Louis bay; no incline up the ridge.

No Lester park to spoon in the dark; no big automobiles,

Not even a bike—every man did hike; them days we eat [ate?] square meals,

A restaurant or boarding house looked good, but by the way,

They are now out of date—we all want to eat at the St. Louis big, swell cafe.

Just one main road was all we had, and the scally to St. Paul.

Every man used an axe; we had no whalebacks—McDougall and Hill looked small.

But Jim Hill has growed [sic], he controls [sic] each road, down east and way out West,

And they tell me he controls the sea—ask Jim, he can tell you best.

I remember quite well and in song I tell how the Manistee went down,

With Catain [sic] McKay and crew that sailed from the Zenith Town,

And the Hulbert too sank with her crew far out from any shore,

In the water’s deep they all do sleep—we shall never see them more.

I miss each one of my old friends gone, tho [sic] many still remain,

Soon we shall meet each other to greet [sic], tho we must part again,

This spring I’ll call and see you all and view your city grand,

They say you’ve growed beyond Herman town road and you are still annexing land.

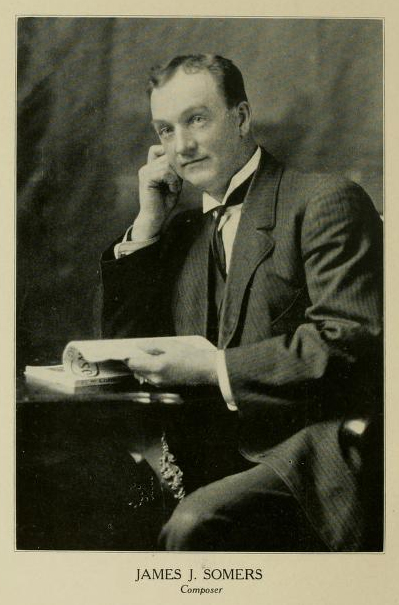

We return this month to this fascinating 1913 book of songs and poems by James J. Somers for one of his several lyrics set in Duluth. Like “The Zenith of the West” that I wrote about a couple months ago, “Duluth in Eighty-Two” is chock full of interesting details about Duluth in the late 1800s. We have Lester Park and the aerial bridge here again along with the “incline”—Duluth’s dramatic Incline Railway that was built in 1891 and gave easy access to the city’s beautiful Superior view.

The tragic shipwrecks of the Manistee and Hulbert both happened in 1883, soon after Somers arrived in town (he wrote another song entirely about the wrecks that I’ll share later). The Captain [Michael] Norris, mentioned in the first verse here, was a survivor of the 1874 Superior shipwreck of the Lotta Bernard.

“Duluth in Eighty-Two” also presents some unfamiliar slang. I haven’t figured out what the “scally to St. Paul” might have been (train? stagecoach?). “Nix come arouse” in the first verse was new to me too. Fred L. Holmes, in Old World Wisconsin, writes that, in German Milwaukee “’nix come erous’ is a customary byword for [the German] ‘nichts kommt heraus.’” The September 23, 1937 Perry Daily Journal of Perry, Oklahoma translates the original German phrase “nichts kommt heraus” as “nothing comes forth” but says that in the early 1800s the phrase became vulgarized in German America to “nix come erous” with the meaning shifting to “there’s nothing to it.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language called nix come erous a German loan-phrase “in decay” that (in 1921) was “familiar to practically all Americans.”

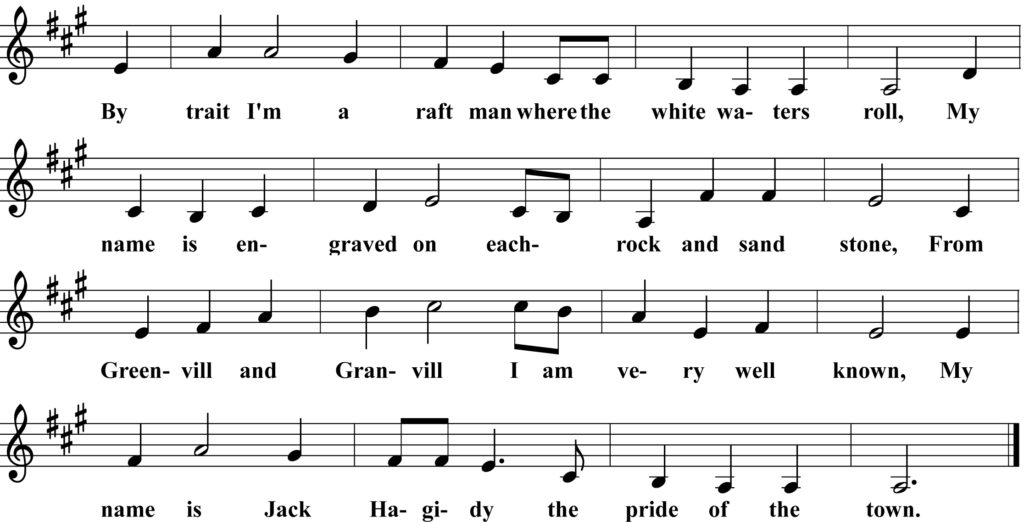

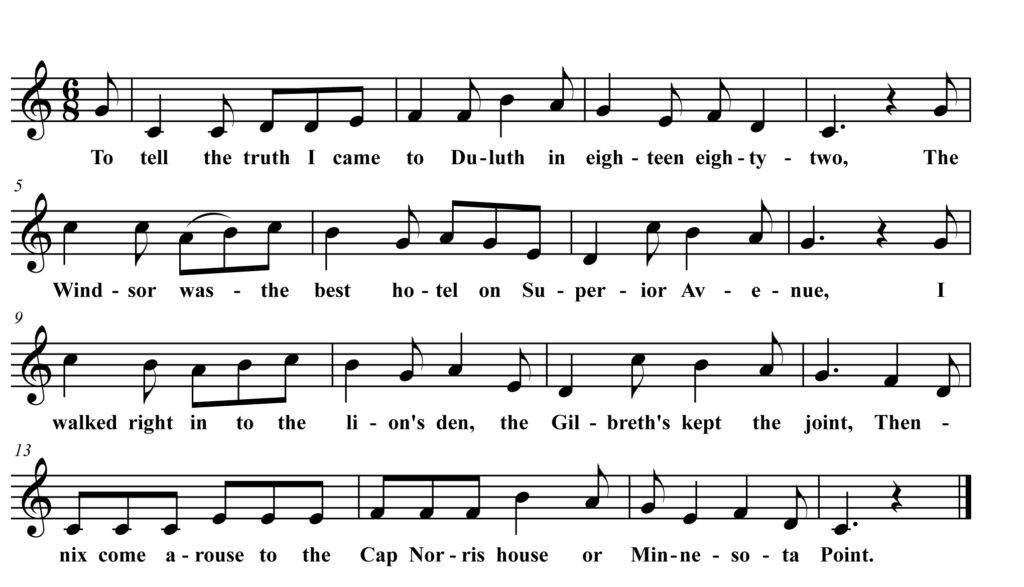

Since Somers’ book does not provide any melodies, I used a tune collected by Franz Rickaby in 1920s Eau Claire from Elide Marceau Fox who used it for the song “Johanna Shay.” I think it fits “Duluth in Eighty-Two” quite well.