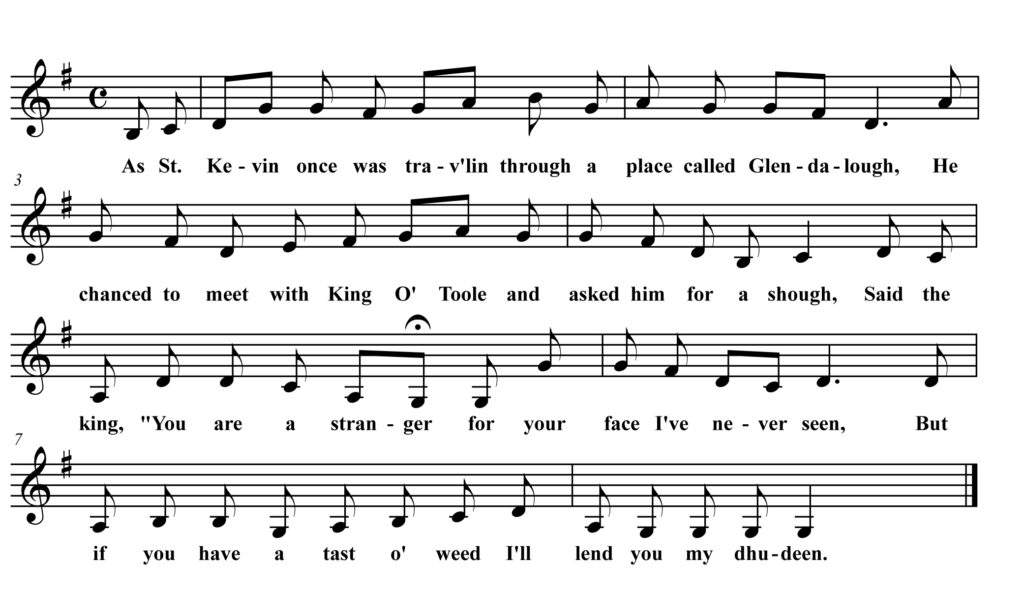

Saint Kevin and the Gander

As Saint Kevin once was travelling through a place called Glendalough,

He met with King O’Toole and he asked him for a shough,

Says the King “You are a stranger and your face I’ve never seen,

But if you want a taste of weed I’ll lend you my duidin.

While the Saint was kindling up his pipe the monarch gave a sigh,

“Is there anything the matter” says the Saint, “that makes you cry?”

Says the King “I had a gander, that was left me by my mother,

And the other day he cocked his toes with some disease or other.”

“Are you cryin’ for the gander? You unfortunate old goose,

Dry up your tears, in frettin’, sure, there’s ne’er a bit o’ use,

As you think so much about the bird, if I make him whole and sound?

Will you give to me the taste o’ land the gander will fly around?”

“In troth I will, and welcome,” said the king, “give what you ask,”

The Saint bid him bring out the bird and he’d begin the task,

The king went into the palace to fetch him out the bird,

Though he’d not the least intention of sticking to his word.

Saint Kevin took the gander from the arms of the King,

He first began to tweak his beak and then to stretch his wing,

The gander he rose in the air, flew sixty miles around,

“I’m thankful to your majesty for that little bit of ground.”

The King to raise a ruction he called the saint a witch,

And he sent for his six big sons to heave him in the ditch,

“Ná bac leis,” says Saint Kevin, “I’ll soon settle these young urchins,”

So he turned the king and his six sons into the seven churches.

Thus King O’Toole was punished for his dishonest doings,

The Saint he left the gander there to guard about the ruins,

If you go there on a summer’s day between twelve and one o’clock,

You’ll see the gander flying round the Glen of Glendalough.

Now I think there is a moral attached unto my song,

To punish men is only right whenever they do wrong,

For poor men they may keep their word much better than folks grander,

For the King begrudged to pay the Saint for curing his old gander.

This is one of two Saint Kevin of Glendalough songs that made their way into tradition. The other, sometimes called “The Glendalough Saint,” (Roud 8001) was sung by the Dubliners and Brendan Behan. The story of Saint Kevin, King O’Toole and the gander (Roud 17152) was sung by legendary Clare musician Micho Russell and others.

The only North American version I am aware of is a very small fragment, a bit of verses five and six above, sung in New Brunswick by the great woods singer Angelo Dornan. Dornan told Helen Creighton his father used to sing the complete song. You can hear Dornan’s fragment under the title “Gander and the Saint” at the wonderful Nova Scotia Archives site. From the fragment, his melody seems to be a version of that used by Limerick singer Con Greaney for “Carlow Town” so I used Greaney’s melody to fill in the blanks here.

Versions of this text were printed in Dublin as early as 1845 (Dublin Comic Songster). A writer with the initials F. P. R. put the text in the “Questions and Answers” section of the New York Times of January 5, 1908 with the following attribution:

The poem of Saint Kevin and King O’Toole was written by Thomas Shalvey, a market-gardener in Dublin, who used to write poems for James Kearney, a vocalist who used to sing at several music-halls and inferior concert rooms in Dublin a good many years ago. Kearney was very popular and some of his best songs were written by Shalvey.

It appears, with the same attribution, in The Humour of Ireland which was published in New York that same year. I incorporated Dornan’s fragment into the New York Times text above.

The song seems certain to have originated among street singers in Dublin in the mid 1800s. Dr Catherine Ann Cullen, a UCD Postdoctoral Fellow with Poetry Ireland, is currently researching and writing about Shalvey, Kearney and other fascinating 19th century Dublin street poets and balladeers and her excellent blog gives more details on the world in which this song emerged.