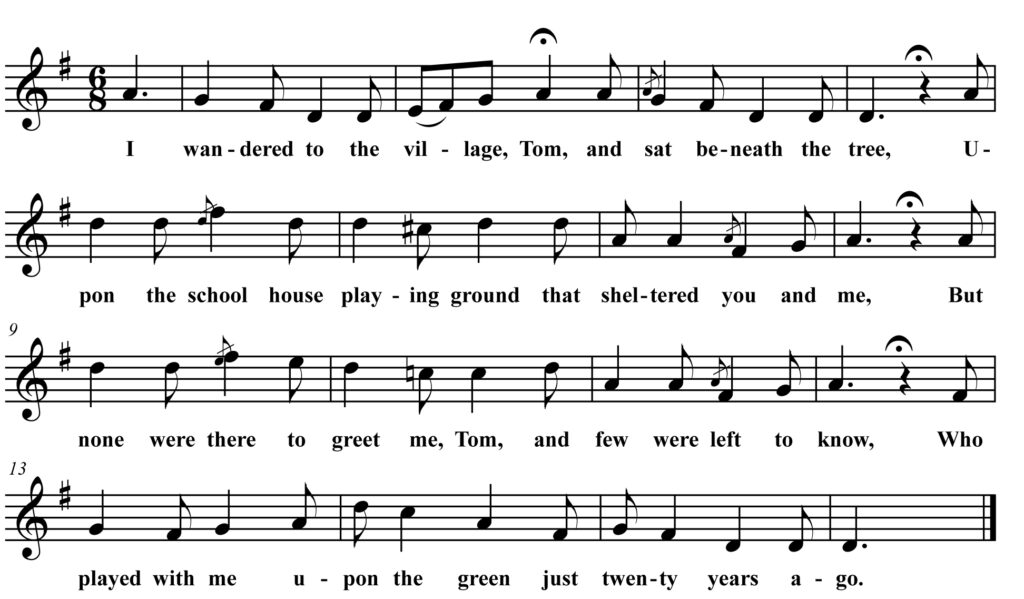

Just Twenty Years Ago

I wandered to the village, Tom, and sat beneath the tree,

Upon the school house playing ground, that sheltered you and me,

But none were there to greet me, Tom, and few were left to know,

Who played with me upon the green, just twenty years ago.

The grass is just as green, dear Tom; barefooted boys at play,

Were sporting just as we were then, with spirits just as gay,

But the master sleeps upon the hill, which, coated o’er with snow,

Afforded us a sliding place, just twenty years ago.

The river’s running just as still, the willows on its side,

Are larger than they were, dear Tom, the stream appears less wide

The grape vine swing is ruined now, where once we played the beau,

And swung our sweethearts—pretty girls—just twenty years ago.

The old school house is altered some, the benches are replaced,

By others very like the ones our penknives had defaced,

The same old bricks are in the walls, the bell swings to and fro,

Its music’s just as sweet, dear Tom, as twenty years ago.

The spring that bubbled ‘neath the hill, close by the spreading beach,

Is very high—’twas once so low—that I could scarcely reach,

And stooping down to get a drink, dear Tom, I started so!

To see how much that I was changed, since twenty years ago.

Close by this spring, upon an elm, you know I cut your name,

Your sweetheart’s just beneath it, Tom, and you did mine the same,

Some heartless wretch has peeled the bark, ’tis dying sure, but slow,

Upon the graves of those we loved, just twenty years ago.

My heart was very sad, dear Tom, and tears came in my eyes,

I though[t] of her I loved so well, those early broken ties,

I visited the old churchyard, and took some flowers to strew,

Upon the graves of those we loved, just twenty years ago.

Some now in that churchyard lay, some sleep beneath the sea,

But few are left of our old class, excepting you and me,

And when our time shall come, dear Tom, and we are called to go,

I hope they’ll lay us where we played, just twenty years ago.

Roud no: 765

We return this month to the book Jim’s Western Gems, a collection of songs and poems self-published in Minneapolis in 1913 by James J. Somers, a second-generation Irish-American born in the Georgian Bay region of Ontario. I shared five of Somers’ own compositions last year but the (text-only) book also includes some traditional songs including the above text.

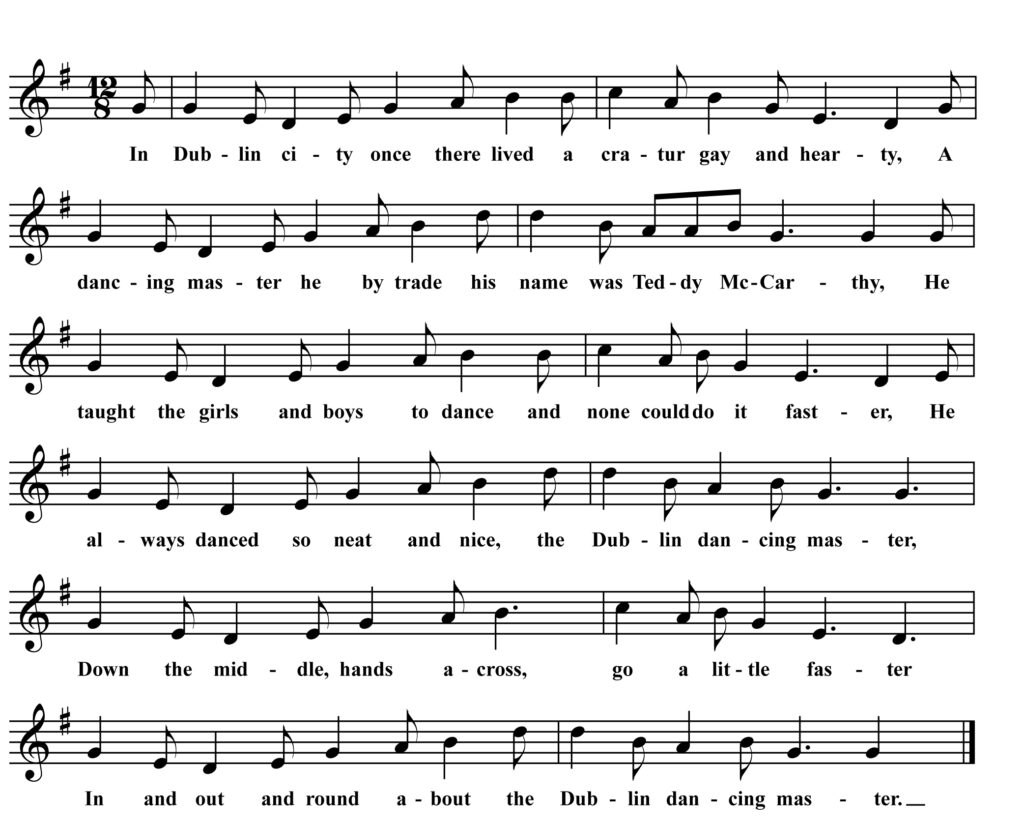

Edward “Sandy” Ives collected the nostalgic “Twenty Years Ago” from John Banks of Prince Edward Island in 1968 and published that version in the book Drive Dull Care Away. Banks used a version of the “Banks of the Nile” melody for the song. “Banks of the Nile” was sung in Minnesota by Michael Dean so, above, I have wed the Somers text with Dean’s melody for a fully Minnesotan version!

The song is likely of American origin and it appears in published song books at least as early as 1859.