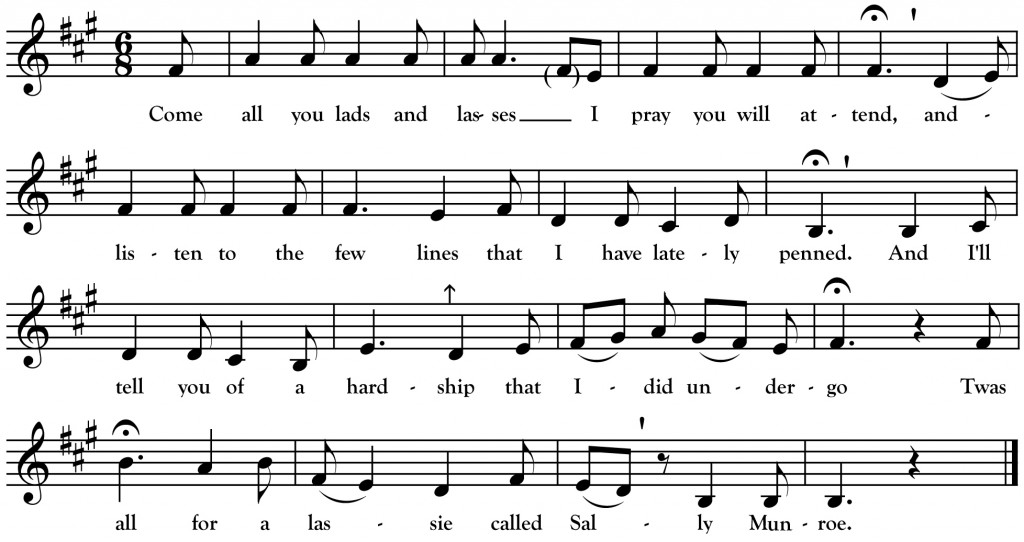

Young Sally Munroe (Laws K11)

Come, all you lads and lassies, I pray you will attend,

And listen to these few lines that I have lately penned,

And I’ll tell you of the hardships that I did undergo,

’Twas all for a lassie called Sally Munroe.

My name it is Jim Dixon, I’m a blacksmith by trade,

And ’twas in the town of Erie where I was born and raised;

From that town to Belfast to work I did go,

A distance in the country from Sally Munroe.

But I promised that fair lady a letter I would send,

And I gave it to a comrade I took to be my friend,

But instead of being a friend of mine, he proved to be my foe,

For he never gave that letter to young Sally Munroe.

But he told her old mother for to beware of me,

That I had a wife in a strange country;

Then says her old mother, “If what you say be so,

He never shall enjoy my young Sally Munroe.”

It was two years and better and never did I hear

A word from the lassie that I once loved so dear,

Till one bright summer morning down by a shady row,

It was there I by chance did meet young Sally Munroe.

I says, “My bonnie lassie, if you’ll gang along wi’ me,

In spite of our auld parents it’s married we will be.”

She says, “I have no objections along with you to go,

For I know you will prove loyal to your Sally Munroe.”

It was in a coach from Norwich to Belfast we did go,

And there I was married to young Sally Munroe;

There was a ship at Williams’ Point all ready to set sail,

With five hundred passengers, their passage all were paid,

I paid down our passage for Quebec also,

And there I did embark with Sally Munroe.

We sailed down the river with a sweet and pleasant gale,

And left our old parents behind to weep and wail,

While many were the salt tears that down their cheeks did flow,

Oh, I was quite happy with young Sally Munroe.

About four in the morning came on a dreadful blow,

Our ship she struck a rock and to the bottom she did go,

With five hundred passengers that were all down below,

And among that great number I lost Sally Munroe.

It was from her old parents that I stole her away,

And that will shock my conscience for many a long day;

It was not for to injure her that ever I did so,

And I’ll mourn all my days for young Sally Munroe.

———————————————————————–

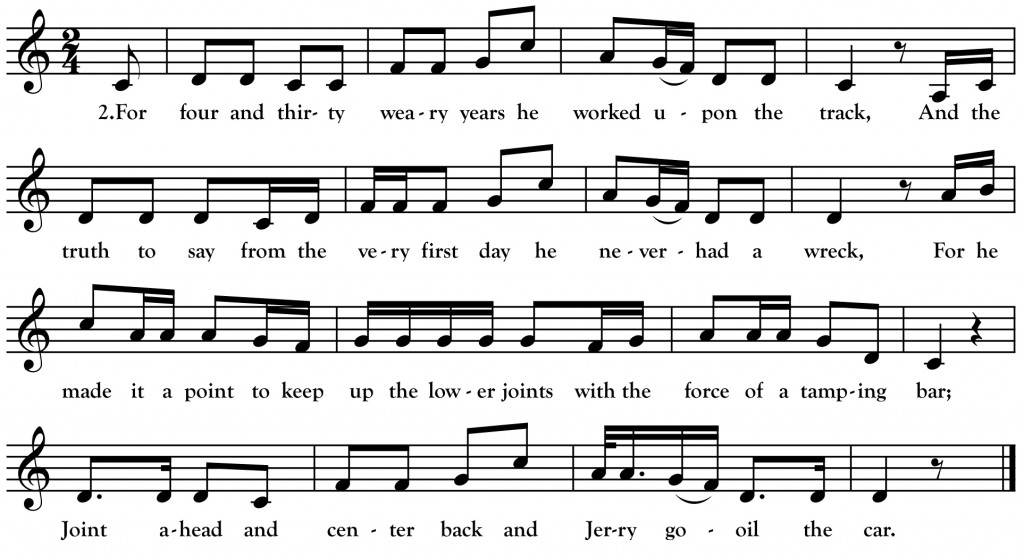

This month’s song is another for which I transcribed the melody from a 1924 wax cylinder recording of Minnesota singer Mike Dean. The text is, again, from Dean’s 1922 songster The Flying Cloud. The song is a rather rare one dating back to the 1830s when it was printed as a broadside (cheap song lyric sheets sold on the street by singers) in northern England and Scotland.* It was likely inspired by an actual event: the 1830 shipwreck of the ship “Newry” which sailed from Newry town with 400 Irish emigrants aboard bound for Quebec but wrecked off Bardsey Island near the Welsh coast where 100 perished. In some of those early broadside versions, Jim Dixon is born in Ayr, Scotland, goes to Belfast to work where he meets Sally and then sails from Newry but shipwrecks en route to Quebec.

The song crossed over to North America where it was collected mainly in Newfoundland and the Canadian Maritime Provinces. Place names vary between most versions. Dean’s version is special because it is the only one collected from a Great Lakes region singer. Also, the abundant place names in Dean’s might indicate it came from southeastern Ontario. Fort Erie, Belfast, Norwich and Williams’ Point are all places in that part of Canada.

This was an exciting one to hear on the recently rediscovered cylinder recordings! Dean has a very striking melody for the song which is different than any other I have found.

*For a detailed discussion of early printings of Sally Munro see Roly Brown’s article on Sally Munro

_________________________________________________

More detailed information on this song from the Traditional Ballad Index