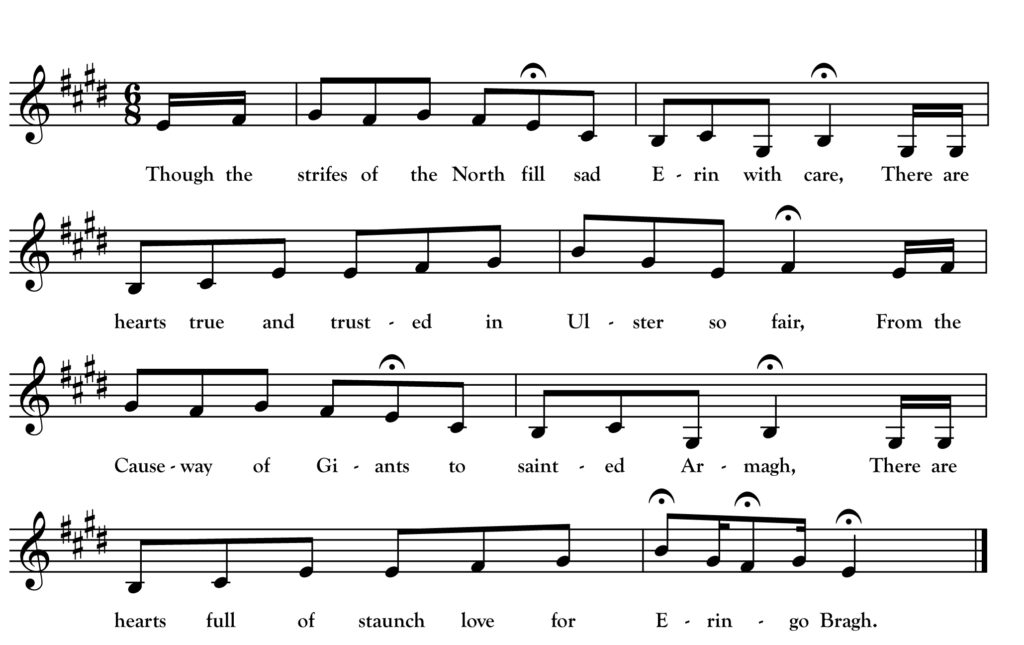

The Four Provinces

Though the strifes of the north fill sad Erin with care,

There are hearts true and trusted in Ulster so fair,

From the Causeway of Giants to sainted Armagh,

There are hearts full of staunch love for Erin go Bragh.

Chorus:

Land of the west, fairest gem of the sea,

The home of the brave, though not of the free,

Ever loving though tearful, ah, who would not draw,

The last drop of his life’s blood for Erin go Bragh.

From Tralee to Kinsale there is patriot ground,

With cities of beauty fair Munster is crowned,

With Killarney’s bright lakes there are none to compare,

And the homes of the South are bright, merry and fair.

In the vale of lovely Leinster how proudly we find,

The charms of the North, South and West are combined,

With Wicklow’s fair mountains that top the blue sea,

The queen of all cities is Dublin machree.

Of all earthly delights the sweet West has but few,

But Connaught was faithful and Connaught was true,

And the same spirit lives in the west as of old,

Bold Connaught was faithful when Ireland was sold.

We take a break from the songs of Michael Dean this month for a rare and intriguing song from Mayo-born singer Dominic Caulfield who lived in St. Paul. Charlie Heymann recently found a tape recording of Dominic singing some of his songs for Tom Dahill, Barbara Dahill and John Curtin around 1976 in a room upstairs from MacCafferty’s Pub on Grand Avenue. The above song appears on the recording.

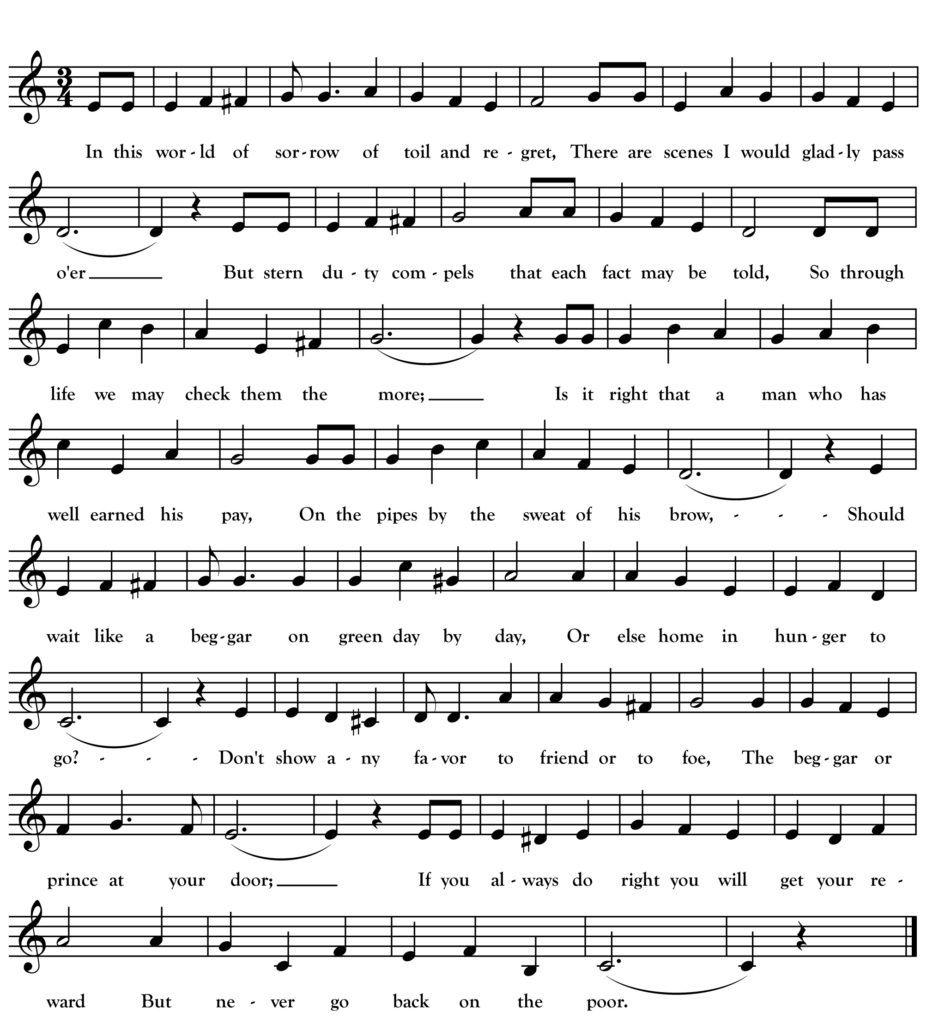

Dominic called this song “The Strifes of the North” but after some intensive searching I was able to locate a text-only version of it under the title “The Four Provinces” in Well-Known Irish Songs, a scarce songbook published in 1924 by Irish Industries Depot, Inc. Thanks to a copy digitized by Harvard, the book’s text is available online. Other than Dominic and the text in Well-Known Irish Songs, I have found no trace of this one.

I hope to learn more about Dominic’s life here in St. Paul (he had siblings here and one sister came about 1905 so my guess is that he immigrated around that time). On the recording he says he lived first with a brother in the Midway neighborhood before moving to Selby Ave.

We do know he was born in County Mayo. This song, though it praises the patriotism of all four provinces, seems to be from a Dubliner’s perspective. The version in Well-Known Irish Songs. Has “In my own lovely Leinster.” I kept Dominic’s verse order above but changed some lines to match the print version when the meaning was clearer. The melody is from Dominic though the transcription does little to capture his light and leisurely singing style. I hope to make the recording available through the McKiernan Library website soon!