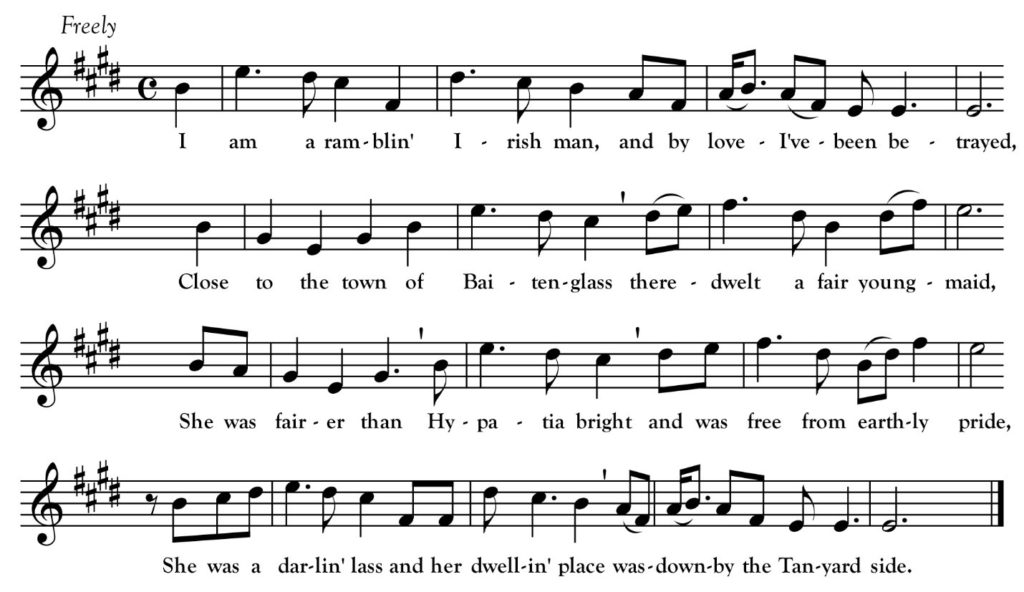

Down By the Tanyard Side

I am a rambling Irishman, and by love I’ve been betrayed,

Close to the town of Baitenglass there dwelt a fair young maid,

She was fairer than Hypatia bright and was free from earthly pride,

She was a darlin’ lass and her dwellin’ place, was down by the tanyard side.

Her lovely hair in ringlets rare, lay on her snow-white neck,

And the tender glances of her eyes, would save a ship from wreck,

Her two red lips so smiling and, her teeth so pearly white,

Would make a man become her slave, down by the tanyard side.

I courteously saluted her, as I viewed her o’er and o’er,

And I said “Are you Aurora bright, descended here below?”

“Oh no, kind sir, I’m a maiden poor,” she modestly replied,

“And I daily labor for my bread down by the tanyard side.”

So for twelve long months I courted her, ’til at length we did agree,

For to aquaint her father, that married we would be,

But ’twas then her cruel father, to me proved most unkind,

Which made me sail across the sea, and leave my love behind.

Farewell to my aged parents, to you I bid adieu,

I’m crossing o’er the ocean, all for the sake of you,

But if ever I return again, I will make this girl my bride,

And I’ll roll her in my arms, down by the tanyard side.

During a lifetime living in the Adirondack mountains of New York state, Sara Cleveland (1905-1987) gathered and sang songs from her Scottish and Irish family and broader community. She eventually compiled a notebook of over 600 songs. Her granddaughter Colleen Cleveland grew up learning Sara’s songs and tagging along with her grandmother, a cherished singer during the folk revival years, to folk festivals and other events. I had the good fortune to meet Colleen and hear her sing at a couple singing events out east and her singing and passion for the songs are very inspiring!

Another upstate New York singer and friend, Dave Ruch, has teamed up with Colleen Cleveland on a wonderful new project to get people singing old songs from the repertoire of Colleen’s amazing grandmother. You can learn more about their “New Audiences for Old Songs” here. One part of the effort is a collection of 75 Cleveland family songs (with audio recordings from Sara or Colleen as well as transcriptions) shared on the site in hopes that current musicians will create their own versions.

Above is my own transcription of Sara Cleveland’s singing of the Irish broadside ballad “Down By the Tanyard Side”—one of the songs offered up as part of the project. Cleveland’s version is quite similar to that printed by Colm Ó Lochlainn in his 1939 Irish Street Ballads. Longford-born American stage performer Frank Quinn recorded a similar text with a different melody in New York City circa 1926. There is another version in a book of songs from Pennsylvania that I do not have on my shelf yet but the only other “north woods” version I have located is one collected by Helen Creighton in Nova Scotia. Cleveland’s “Baitenglass” is given as Baltinglass in Ó Lochlainn which is the name of town in southwest County Wicklow.