My Emmett’s No More

Despair in her wild eye, a daughter of Erin,

Appeared on the cliffs of the wild, rocky shore,

Loose in the wind flowed her dark, streaming ringlets,

Heedless she gazed on the dread surge’s roar.

Loud rang her harp in wild tones of despairing,

The time passed away with the present comparing,

And in soul-thrilling strains deeper sorrow declaring,

She sang Erin’s woes, for her Emmett’s no more.

Ah, Erin, my country, your glory’s departed,

For tyrants and traitors have stabbed thy heart’s core,

Thy daughters have laid in the streams of affliction,

Thy patriots have fled or lie stretched in their gore.

Ruthless ruffians now prowl through they hamlets forsaken,

From pale, hungry orphans their last morsel have taken,

The screams of thy females no pity awaken

Alas! My poor country, your Emmett’s no more.

Brave was his spirit yet wild as the Brahmin,

His heart bled in anguish at the wrongs of the poor,

To relieve their hard sufferings he braved every danger,

The vengeance of tyrants undauntedly bore.

Before him the proud, titled villains in power,

Were seen though in ermine, in terror to cower

But, alas! He is gone—he’s a fallen young flower,

They have murdered my Emmett—my Emmett’s no more.

Roud no: 34010

Thanks to the wonders of the archive at newspapers.com, I recently discovered a new source for Minnesota folk songs! On most Sundays between October 1923 and January 1925, the Minneapolis Journal ran a column called “The Old Songs Exchange: Words That Journal Readers Ask For.” Similar to the “Old Songs That Men Have Sung” column in Adventure Magazine I have used in my research before, the Old Songs Exchange was full of fascinating folk and stage song texts submitted by readers of the paper—complete with, in most cases, attribution for who sent in the words.

The Sunday, November 2, 1924 column includes “My Emmett’s No More,” a somewhat rare song commemorating Robert Emmett and the 1798 uprising in Ireland. Unfortunately, the Journal gave no attribution for this one. The four other song texts printed that day were supplied by Newman L. Deusen of Brunswick, Ohio; Mrs. Laura M. Klinefelter of Steele, North Dakota; and Mrs. Lula I. Godwin of Minneapolis so it is possible that the Emmett song came from one of them. The text in the Journal does seem to be from someone’s memory as it is missing a couple lines from what would have appeared in a songster or broadside (many songsters in both Ireland and US did print the song). See below for the text as it appeared in the Minneapolis Journal.

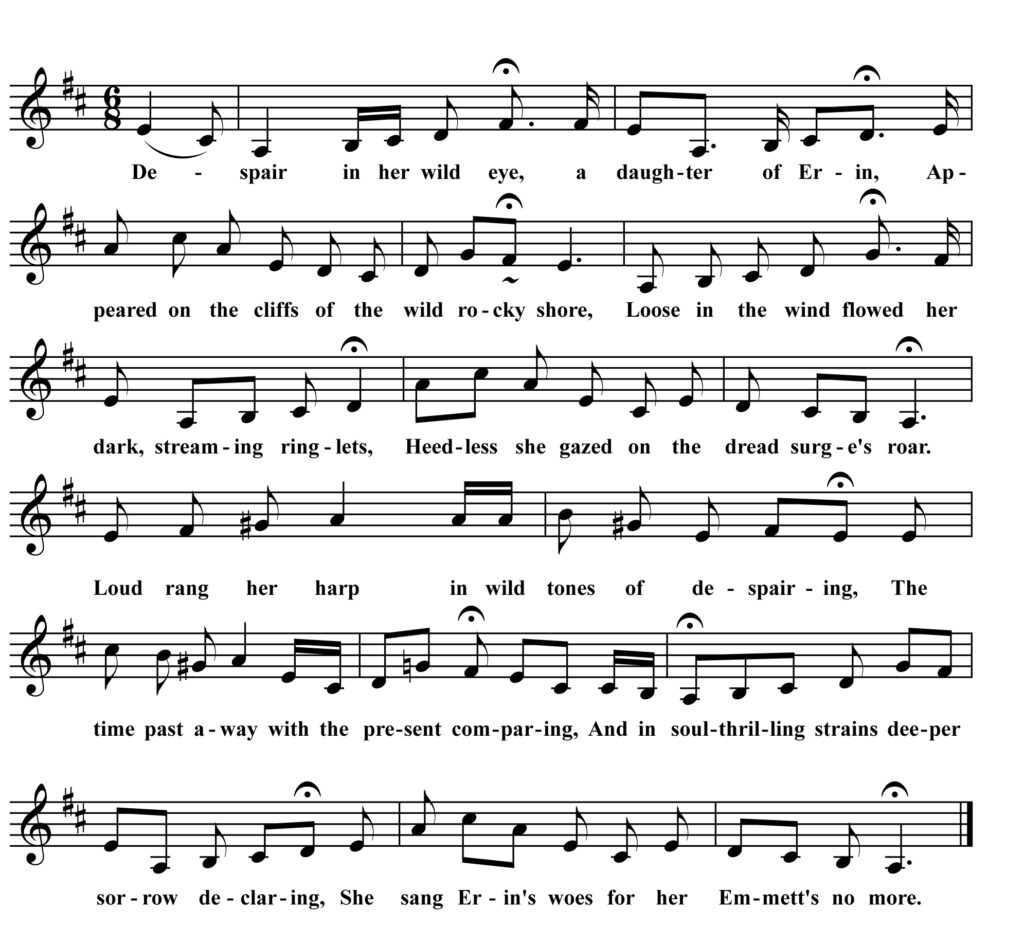

I have married the Minneapolis-printed text to the melody sung by Irish singer (and dancer) Páidí Bán Ó Broin whose rendition appears in the Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann digital archive. Ó Broin was part of the Comhaltas touring group that visited Minnesota in 1976 and stayed with Lucy and Jack Fallon in St. Paul. I also filled in a couple missing lines using a version printed by Terry Moylan in The Age of Revolution in the Irish Song Tradition.