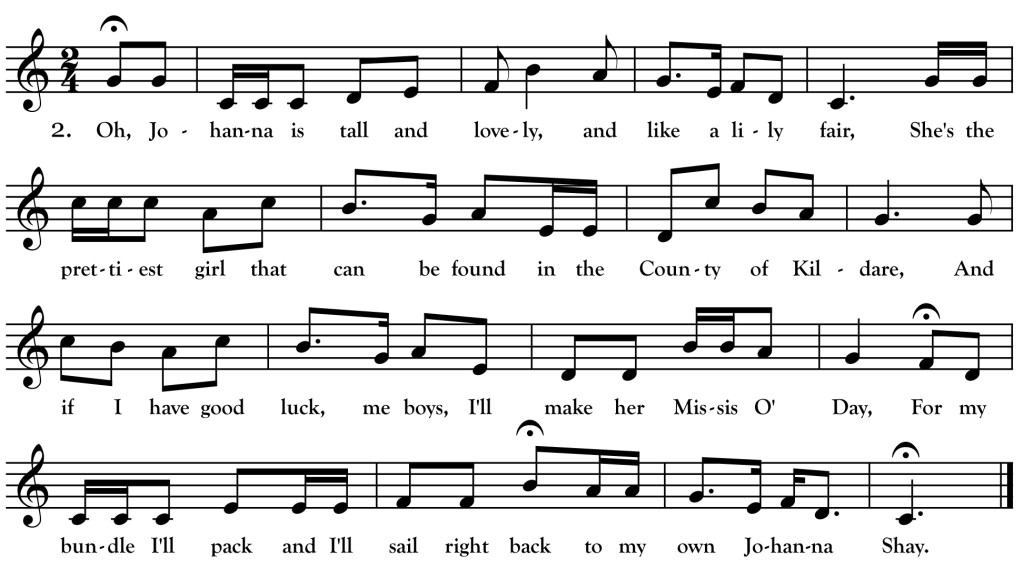

Johanna Shay

In the Emerald Isle so far from here across the dark blue sea,

There lives a maid that I love dear and I know that she loves me,

With roguish eyes of Irish blue her cheeks like dawn of day,

Oh, the sunshine of my life she is, my own Johanna Shay.

Oh, Johanna is tall and lovely and like a lily fair,

She is the prettiest girl that can be found in the County of Kildare,

And if I have good luck, me boys, I’ll make her Mrs. O’Day,

For my bundle I’ll pack and I’ll sail right back to my own Johanna Shay.

There’s a bird in yonder garden singing from a willow tree,

That makes me think of Johanna when she used to sing to me;

When side by side o’er the mountains or by the lake we strolled,

And her cheeks would flush with an honest blush whenever a kiss I stole;

Though the ocean rolls between us, if harm was in her way,

I would jump right in and boldly swim to my own Johanna Shay.

______________________________________________________________

This summer marks the 90th anniversary of a productive three-week song collecting trip around Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin by folksong collector Franz Rickaby. Rickaby had just finished his final year as English professor at the University of North Dakota in 1923 and was about to move to the warmer climes of California in an attempt to ease the pain of rheumatic fever—the disease that tragically cut his life, and the preservation of Upper Midwestern traditional folksong, short. He gathered songs first in Bemidji and then met with prolific singer Michael Dean in Virginia, MN before heading to Eau Claire, WI and Bayport, MN. The above song text comes from Dean’s repertoire as printed, not by Rickaby, but by Dean in his self-published songster The Flying Cloud. Rickaby did not transcribe “Johanna Shay” from Dean’s singing, but he did jot down the melody used for it by Eau Claire singer Elide Marceau Fox. I married Fox’s melody to Dean’s text above.

I have found not one single other instance of this song in any other collection of texts, transcriptions or recordings—remarkable in this age of searchable digital archives and well-researched databases of folk song! Fox’s melody (and some of the poetry) hints at a connection to the Irish Music Hall song-writers of the 1800s. Whether it was born on the stage or was simply in imitation of that style we may never now. Still, quite a nice little song I think.