Young Monroe

Come all you jolly shanty boys, wherever you may be,

I hope you’ll pay attention and listen unto me,

Concerning a young shanty boy so manfully and brave,

It was on a jam at Garray’s rocks where he met with a watery grave.

It was on a Sunday morning as you will quickly hear,

Our logs were piling mountain high, we could not keep them clear,

When the boss he cries, “Turn out, me boys, with hearts devoid of fear,

To break the jam on Garry’s rocks and for Eagantown we’ll steer.”

Some of them were willing, while others they hung back,

To work upon a Sunday they did not think was right,

Until six of our young Canadians they volunteered to go,

And break the jam on Garry’s rocks with their foreman, young Munroe.

They had not rolled off many logs when the boss to them did say,

“I would have you to be on your guard, for this jam will soon give way.”

Those words were scarcely spoken when the jam did break and go,

And carried away those six young men with their foreman, young Munroe.

When the rest of those young shanty boys they came, the news to hear,

In search of their dead bodies for the river they did steer,

When one of their lifeless bodies found to their sad grief and woe,

All cut and mangled on the rocks was the form of young Munroe.

They took him from his watery grave, combed down his coal-black hair,

There was one fair form among them whose cries did rend the air;

There was one fair form among them, a girl from Saginaw town,

Her tears and cries would rend the skies for her lover that was drowned.

Miss Clara was a noble girl, likewise a raftsman’s friend,

Her mother was a widow living by the river’s bend,

The wages of her own true love the boss to her did pay,

And a liberal subscription she received from the shanty boys next day.

They took and buried him decently, being on the tenth of May,

And the rest of you young shanty boys, it’s for your comrade pray!

It is engraved on a little hemlock tree, close by his head it does grow,

The day and date of the drowning of this hero, young Munroe.

Miss Clara did not survive long to her sad grief and woe;

It was less than two weeks after she, too, was called to go,

It was less than two weeks after she, too, was called to go,

And her last request was granted her, to be laid by young Munroe.

Now, any of you shanty boys that would like to go and see,

On a little mound by the river side there grows a hemlock tree;

The shanty boy cuts the woods all round, two lovers here lie low,

Here lies Miss Clara Dennison and her lover, young Munroe.

This month marks the 100-year anniversary of Irish-Minnesotan singer Michael Cassius Dean sending a copy of his song book, The Flying Cloud, to song collector Robert Winslow Gordon. Accompanied by a brief note on a postcard featuring Virginia, Minnesota’s 10-year-old high school building, this parcel led to one of the earliest audio recordings of traditional music in Minnesota. Twelve months later, inspired by this collection of 166 songs from Dean’s repertoire, Gordon went in search of Dean with his wax cylinder recording machine in tow.

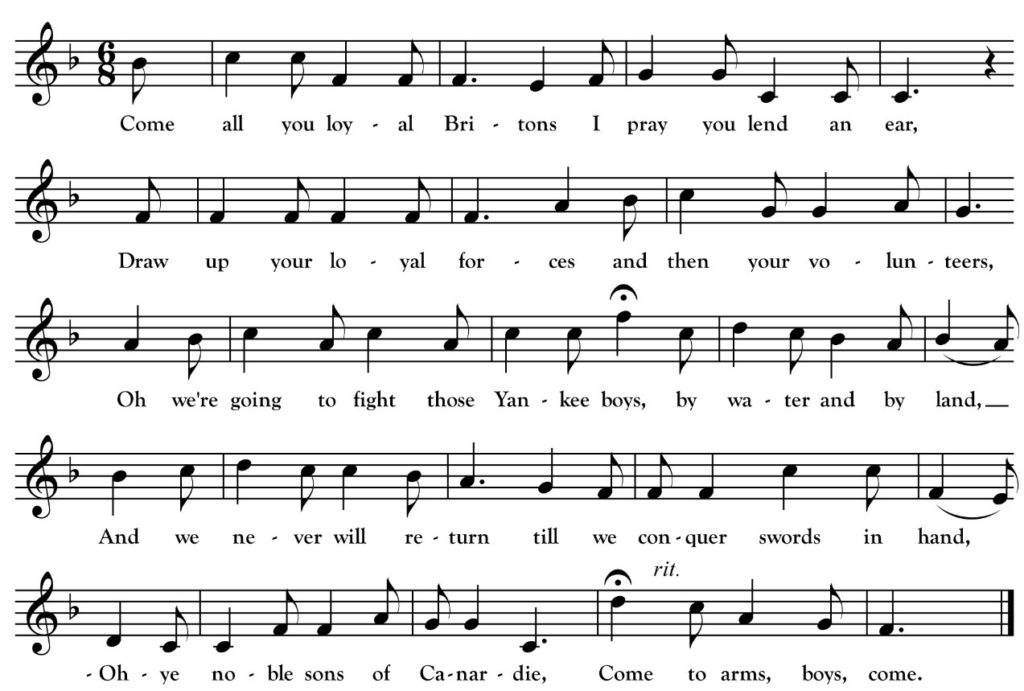

Dean’s version of “Young Monroe” was one of the songs recorded by Gordon in September 1924 and the above transcription is my own made from the Gordon recording. The full text above comes from Dean’s book.

“Young Monroe,” often titled “The Jam at Gerry’s Rocks,” was one of the most widely sung come-all-ye type songs about logging work. Versions were collected all over the US and Canada. For a nice recording, check out this one of Ted Ashlaw. Ashlaw lived in a similar part of northern New York to where Dean grew up and his melody, though similar to Dean’s, has some nice twists to it.