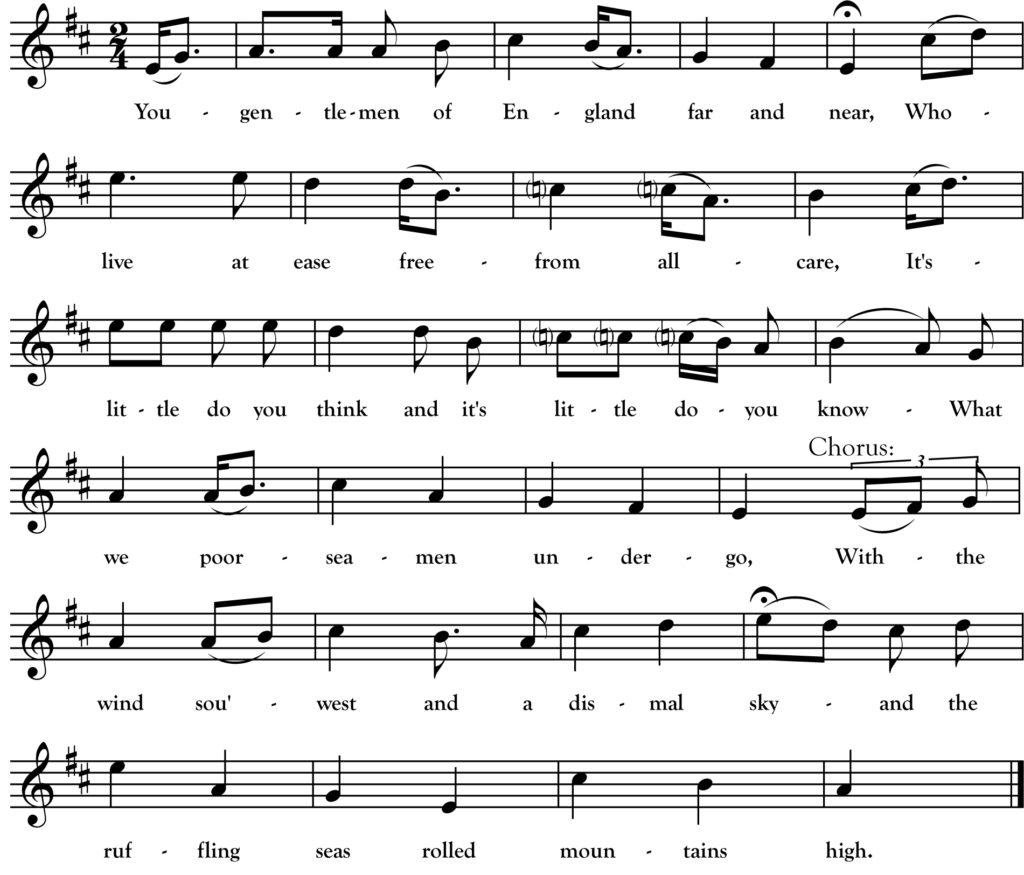

The Wind Sou’west

You gentlemen of England far and near,

Who live at ease free from all care,

It’s little do you think and it’s little do you know,

What we poor seamen undergo,

Chorus:

With the wind sou’west and a dismal sky,

And the ruffling seas rolled mountains high.

On the second day of April, ‘twas on that day,

When our captain called us all away,

He took us from our native shore,

While the wind sou’west and loud did roar.

On the fifth day of April, ‘twas on that day,

When we spied land on the lo’ward lay,

We saw three ships to the bottom go,

While we, poor souls, tossed to and fro.

On the sixth day of April, ‘twas on that day,

When our capstan and foremast washed away,

Our mast being gone, the ship sprang a leak,

And we thought we should sink in the watery deep.

The second mate and eighteen more,

Got into the longboat and rowed for shore,

But what must have been for their poor wives,

A-losing their husbands’ precious lives?

On the seventh day of April, ‘twas on that day,

When we arrived in Plymouth Bay,

What a dismal tale had we for to tell,

Of how we acted in the gale.

We return this month to the fantastic repertoire of singer Carrie Grover (1879-1959) who grew up in Nova Scotia and lived her adult life in Maine. “The Wind Sou’west” appears in her published songbook “A Heritage of Songs” where she classifies it as one of her father’s songs. Her father, George Craft Spinney, was born in 1837 and spent many years working on merchant vessels where he learned many sea songs. This song appears to be a variant of an English song dating to the late 18th century often titled “You Gentlemen of England” but Grover’s version is pretty unique with a localized New England reference to Plymouth Bay. No English versions I have seen include a chorus.

Thanks to the incredible work of singer and researcher Julie Mainstone Savas, we now have the website The Carrie Grover Project which includes transcriptions of all the songs in “Heritage of Songs” and more plus some audio recordings of Grover. The site is well worth checking out. There you can hear a recording of Grover singing the above (from which I made my own transcription). In it, Grover makes masterful use of the traditional singer’s trick of singing an “in between” third scale degree – somewhere between major and minor – that, to me, gives the song a perfect haunting quality.