The Dublin Lasses Reel

Between 1910s and 1970s, folk song scholars, collectors and singers transcribed or recorded abundant examples of Irish-influenced traditional singing held over in the Great Lakes region from the days of live-in logging camps and fresh water schooners. The presence of instrumental music in old time Great Lakes logging camps is also well documented in photos and first-hand accounts but, sadly, very few transcribers or recorders bothered to capture any of the tunes!

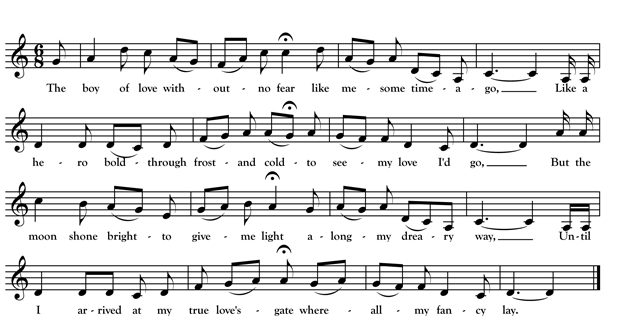

I decided to take a month off from the songs and share an interesting version of an Irish reel (usually called “The Five Mile Chase”) from Beaver Island, Michigan fiddler Patrick Bonner (1882-1973). Bonner’s fascinating fiddle playing was recorded. Alan Lomax recorded a dozen or so tunes from him in 1938 and Ivan Walton a dozen more in 1940. Bonner’s setting of “The Dublin Lasses” was one of some 80 or more tunes recorded between 1950 and the mid-60s by Edward “Edgar” O’Donnell. O’Donnell’s (low fi) recordings of Bonner are available online here.

Patrick Bonner was the son of Black John Bonner, believed to be the first Irishman to arrive on Beaver Island after the fall of the island’s Mormon kingdom in 1856. Black John was born on Rutland Island (=Inis Mhic an Doirn), County Donegal not far from Arranmore (the birthplace of most first generation Irish-Beaver Islanders). His song Patrick was born on Beaver Island and lived there his entire life working as a farmer, logger and sailor and entertaining on his fiddle at “dances, picnics, weddings, and house parties.”[1] Patrick Bonner’s playing is an intriguing blend of Irish fiddle style and a looser, simpler, more “American” approach. I highly recommend looking him up online to hear him for yourself!

[1] Sommers, Laurie Kay, Beaver Island House Party, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1996) 45.