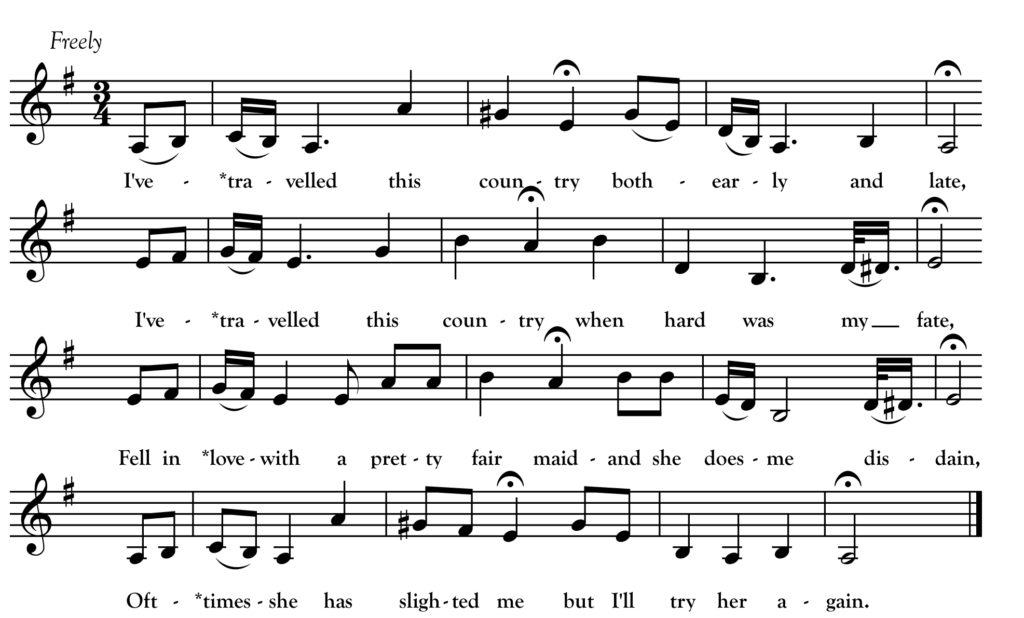

Farewell to Nancy

I’ve travelled this country both early and late,

I’ve travelled this country when hard was my fate,

Fell in love with a pretty fair maid, but she does me disdain,

Oft times she has slighted me, but I’ll try her again.

Oh, your parents are rich, love, and you hard to please,

I would have you take pity on your heart-broken slave,

I would have you leave your father and your mother also,

And through this wide world with your darling boy go.

“Oh, Johnnie, dear Johnnie, such advice will not do,

For leave my own country and to go along with you,

My friends and old sweethearts they would mourn my sad fate,

If I’d leave my own country and go follow a rake.”

Now my love she won’t have me, and away I must go,

To the wide spreading ocean where the salt breeze does blow,

To seek a companion, it is all my design,

Fare you well, dearest Nancy, must I leave you behind?

Fare you well, dearest Nancy, and merry may you be,

I will always think of you wherever you be,

But since you’ve proved unloyal to the one that’s so true,

May the wide spreading ocean separate I and you.

We return to the wonderful repertoire of Nova Scotia/Maine singer Carrie Grover this month for a song you can hear online via the Carrie Grover Project website. Grover’s singing is full of character and nuance and is definitely worth hearing. As I say above, the recording does a far better job of conveying her style than anything I can transcribe (or describe!) here.

Grover’s “Farewell to Nancy” contains some “floating” lines in the first verse that turn up in versions of other songs including “Green Grows the Laurel” and the Scottish Bothy ballad “Airlin’s Fine Braes.” Steve Roud classifies “Farewell to Nancy” along with a song called “Little Susie” that was sung in parts of the southern US. A version of “Little Susie” collected by Max Hunter in Arkansas does share many words with Grover’s song.

It is Carrie Grover’s striking melody that I find most attractive here. I love the big leaps and interesting pitch variances in her performance.