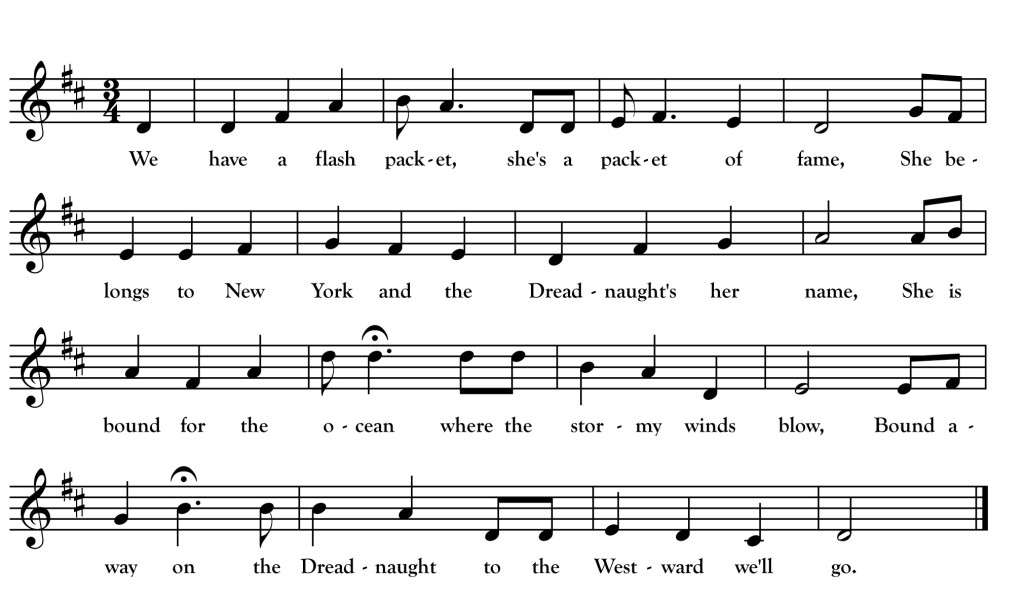

The Clipper Ship Dreadnaught (revisited)

We have a flash packet, she’s a packet of fame,

She belongs to New York and the Dreadnaught’s her name;

She is bound for the ocean where the stormy winds blow,

Bound away on the “Dreadnaught” to the Westward we’ll go.

The “Dreadnaught” is lying at Liverpool dock.

Where the boys and the girls on the pier-heads do flock,

And they give us three cheers as their tears down do flow,

Bound away on the “Dreadnaught” to the Westward we’ll go.

And now we are howling on the wild Irish sea,

Where the sailors and passengers together agree,

For the sailors are perched on the yard arms, you know,

Bound away on the “Dreadnaught” to the Westward we’ll go.

Now we are sailing on the ocean so wide,

Where the great open billows dash against her black side,

And the sailors off watch are sleeping below,

Bound away on the “Dreadnaught” to the Westward we’ll go.

And now we are howling off the banks of New Foundland,

Where the waters are deep and the bottom is sand,

Where the fish of the ocean they swim to and fro,

Bound away on the “Dreadnaught” to the Westward we’ll go.

And now we are safe in New York Harbor once more,

I will go and see Nancy, she’s the girl I adore,

To the parson’s I’ll take her, my bride for to be,

And bid adieu to the “Dreadnaught” and the deep stormy sea.

___________________

This is the first song I am featuring as part of The Lost Forty Project I announced last month. The video is of The Lost Forty (Randy Gosa and I) performing our brand new arrangement of the above song. For the next eleven songs printed in Northwoods Songs, Randy and I will arrange the song and post a video on the first of the month. We are excited to be working with Cliff Dahlberg of Twelve Plus Media who is shooting the videos. You can access these videos and an archive of all previous Northwoods Songs columns and videos here or via my Youtube Channel.

“The Clipper Ship Dreadnaught” was already the focus of a Northwoods Songs post in November 2014. I return to it this month because it was the first song Randy and I chose to arrange for The Lost Forty Project. We based our arrangement on the 1924 field recording of Minnesota singer Michael Dean. The Dean recording will be part of the Minnesota Folksong Collection website I am building.

A central goal of The Lost Forty Project is to inspire others to learn and sing these songs themselves. This could mean singing the song unaccompanied, the way Dean and other woods singers of his generation would have done, or it could also mean creating an accompanied arrangement as Randy and I have done for “The Dreadnaught.” It is my opinion that both are musically satisfying and valuable approaches.

I learned and sang this song unaccompanied first. From that, I found my voice likes pitching it in B (it’s transcribed in D above). For our arrangement, I started by making up a guitar part using an unusual tuning associated with English guitarist/singer Nic Jones: BF#BF#BC#. Randy then created a harmonizing mandola part in CGDG tuning capoed at the 4th fret. I often use a combination of sheet music and the handy voice memo app on my phone to remember bits of my part as I make them up. Randy tends to work more by ear and memory. It is often a labor-intensive (but fun) process to come up with two complementary parts that we both like. Along the way, I decided to drop two verses from Dean’s version and change a few words here and there. I have transcribed it above more or less how I now sing it.

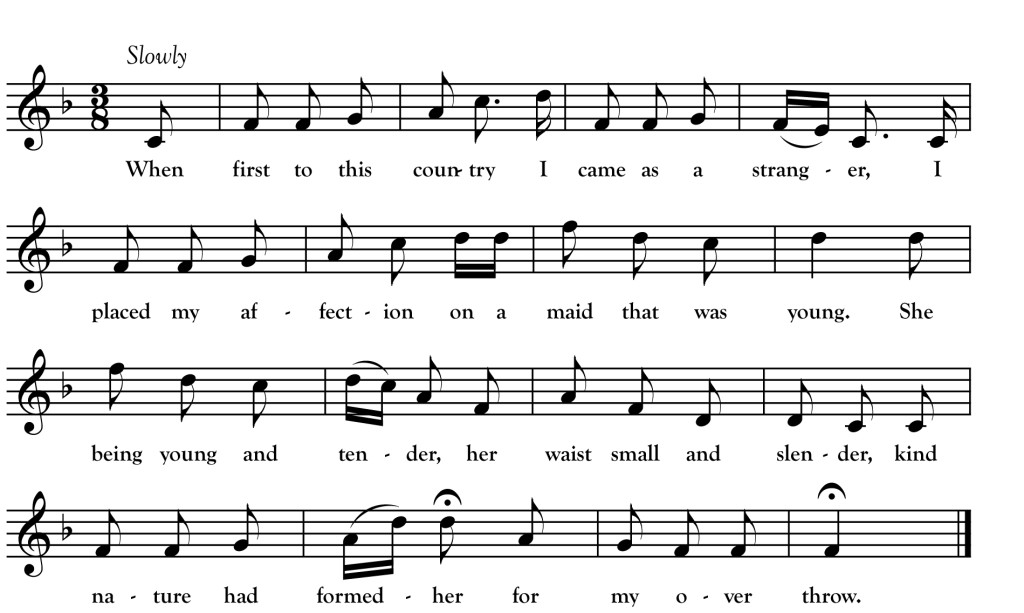

Next month, I will return to giving historical notes in my discussion of another song from the project: “The Crafty Miss.” For those interested in learning how to arrange songs in a style similar to Randy and me, when I launch my Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign this month one incentive I will be offering is a set of guitar and bouzouki/mandola part transcriptions for all twelve songs in the project.

This activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund.