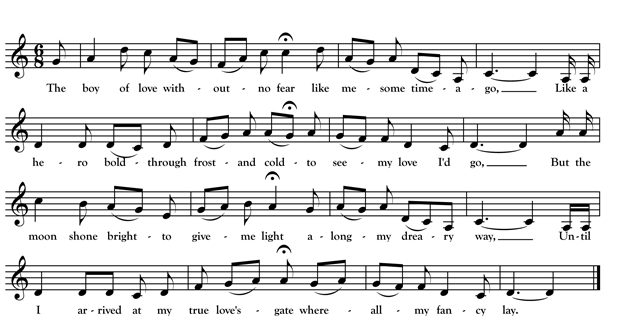

The Boy of Love

The boy in love without no fear like me some time ago

Like a hero bold through frost and cold to see my love I’d go

But the moon shone bright to give me light along my dreary way,

Until I arrived at my true love’s gate where all my fancy lay.

When I arrive at my true love’s gate, my step being soft and low,

She will arise and let me in, so softly I will go,

Saying, “Will you come to my father’s house?” “No dear, but come to your own,

Come with me, love, to the Parson’s and there we’ll be made one.”

“Oh no, oh no kind sir,” said she, “for prudence would not agree,”

“Well, then, sit down along by my side, for I must talk with thee,

For seven long years I have courted you against your parents’ will,

I was always resolved you would be my bride, but now, pretty girl, farewell.

“My ship lies in the harbor all ready to set sail,

And if the wind is from the East we’ll have a favoring gale,

And when I reach Columbia’s shore it is often I will say,

May the Lord above protect my love where all my fancy lay.

We return again this month to another fine Irish song from the repertoire of Minnesota singer Michael C. Dean. Irish song scholar John Moulden has traced this song, well known today in Ireland as “When a Man’s in Love He Feels No Cold,” back to its original composer: County Antrim schoolmaster Hugh McWilliams. McWilliams included “A Man in Love” in his book Poems and Songs on Various Subjects which was published in 1831 in Antrim.

The song entered folk tradition where, over the next hundred years, it gained some words, lost others and was set to several different melodies. Dean’s “Minnesota version” provides evidence of the furthest distance the song traveled from its source.

Since Dean left us only his text, I based the above melody on the melodies used for two other transatlantic versions collected in Marystown, Newfoundland by Maud Karpeles in 1930 and printed in Folk Songs from Newfoundland.