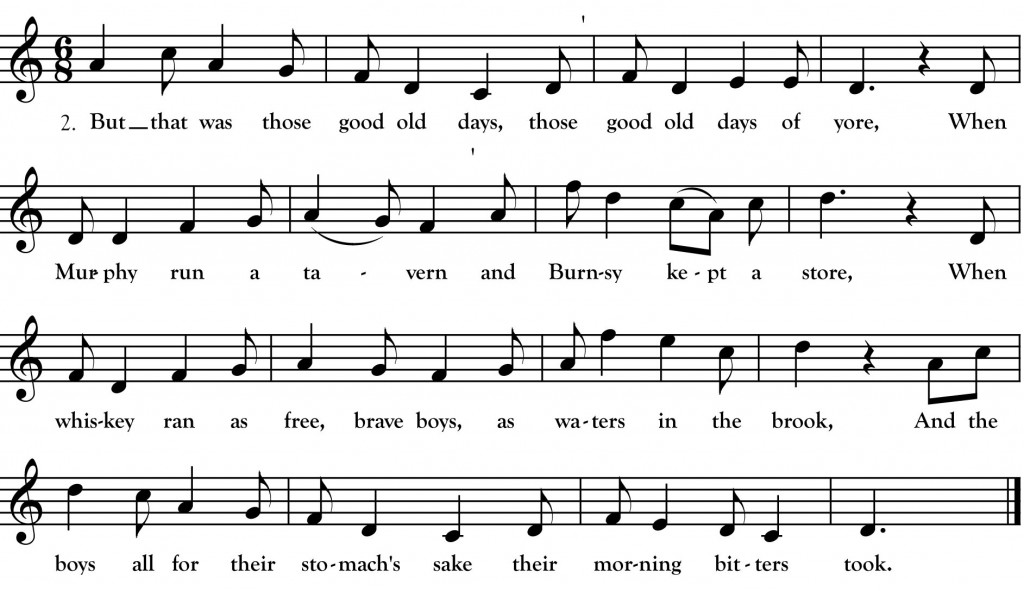

We Are Anchored by the Roadside, Jim

We are anchored by the roadside, Jim, as we’ve oft-times been before,

When you and I were weary from sacking on the shore,

The moon shone down in splendor, Jim, it shone on you and I,

And the little stars were shining when we drank the old jug dry.

But that was those good old days, those good old days of yore,

When Murphy run a tavern and Burnsy kept a store,

When whiskey ran as free, brave boys, as waters in the brook,

And the boys all for their stomach’s sake their morning bitters took.

But times they have now altered, Jim, and men have altered too,

Some have undertaken for to put rum sellers through,

For they say that whiskey’s poison and scores of graves has dug,

Ten thousand snakes and devils have been seen in our old jug.

But never mind such prattle, Jim, though some of it may be true,

We’ll lie where we’re a mind to, together, me and you,

For the drink they call cold water, won’t do for you nor I,

So we’ll haul the cork at leisure, and we’ll drink the old jug dry.

I recently checked out the current exhibit at the Minnesota History Center American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (an exhibit which, I couldn’t help but notice, is being “repealed” on March 16th – just in time for a certain holiday). It reminded me of this song which I transcribed from the singing of Robert Walker. Walker referred to it as an “anti-prohibition song” when he sang it for collector Sidney Robertson-Cowell in Crandon, Wisconsin in 1952. It appears on the record Wolf River Songs. (Robertson-Cowell also recorded Walker’s nephew Pat Ford singing his version of the song which you can hear on the Library of Congress website)

Across the northwoods, there was much opposition to prohibition from men who worked in the lumber industry. For many lumberjacks, drink was seen as a necessary relief from long hours and back-breaking labor. “Sacking,” mentioned in verse one, was certainly thirsty work. Walker explained: “When they was driving logs and high water had put ‘em way out in the marshes someplace, and the men’d have to get right into the water and roll ‘em out into the stream again, — that was sacking, see?”[1] Sacking was made especially harsh by frigid spring waters and huge logs beached far from the open stream by lumber companies’ use of temporary dams. Another Wisconsin lumberman, Robert Nelligan, wrote “There are few kinds of labor more arduous than river driving. We got up about three o’clock in the morning and were at work all day until darkness fell, most of the time wading in icy cold water and sometimes more than wading. Men working under such a strain as this needed stimulants. Whiskey was used and much of it.”[2]

The song’s reference to Murphy’s tavern hints at the prevalence of Irish saloon owners in small northwoods towns like Crandon. In fact, when Irish-American Mike Dean transitioned from working as a lumberjack to buying his own saloon in Hinckley, Minnesota in the 1880s, he was taking up a profession dominated, in Pine County at least, by Irishmen. An 1887 list of Pine County liquor license applicants includes the surnames: Dean, Rourke, Tierney, Hurley, Brennan, Durkan, Connors, Connor and Hennesy![3]

So perhaps it is no coincidence that Dean did not stay long in Pine County after that county joined many other Minnesota counties in voting itself dry in 1915, five years before national prohibition. By 1917 Dean was settled in Virginia, Minnesota which had remained “wet” even though nearby Hibbing (and most of northwestern Minnesota) had gone “dry” along with Pine County in 1915. In fact, some clever songsmith in Hibbing had made another “anti-prohibition” song to the tune of the recent John McCormack hit “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary:”

It’s a long way to Old Virginia, it’s a long way to go,

It’s a long way to Old Virginia, to the wettest town I know,

Farewell, then, oh ye lager, farewell rock and rye,

It’s a long, long way to Old Virginia, when Hibbing goes dry.[4]

[1] Sidney Robertson Cowell, Wolf River Songs (NYC: Folkways LP FE 4001, 1956) 5.

[2] John Emmett Nelligan, A White Pine Empire: The Life of a Lumberman (St. Cloud: North Star, 1969) 33.

[3] Pine County Pioneer, Apr. 15, 1887.

[4] Al Zadon, “Power ‘The Little Giant of the North’,” Mesabi Daily News, Oct. 3, 1976.